Scene One

Ahmed Sabaa al-Leil, a poor young soldier from Egypt’s countryside, had been indoctrinated to view political prisoners as traitors and enemies of the state. Stationed behind prison bars, he witnesses the haunting cries and suffering of political prisoners. The young soldier finds himself in confrontation with the prison ward, and his inner conflict intensifies when he encounters Hussein Wahdan—an imprisoned intellectual from his own village, who had been the first to politically influence Sabaa el-Leil and teach him the ideals of patriotism.

Their reunion in prison is jarring, as Sabaa El-Leil begins to realize that the truth is far from all he had been taught. He could not accept torture as a means of ‘defending the homeland’. To him, it was a crime against humanity. When his friend Hussein dies of snakebite, a form of torture in prison, Sabaa El-Leil, once loyal to authority, is overcome with guilt and seeks revenge for the injustice.

Those were scenes from The Innocent, a 1986 Egyptian film, which critiques state repression and corruption during the aftermath of President Sadat’s economic "open-door" policy and the so-called “Thieves’ Uprising” of 17-18 January 1977. In line with the general atmosphere in Egypt, the film itself was suppressed at the time— remaining banned until 2005, when it was finally screened uncensored for the first time.

Scene Two

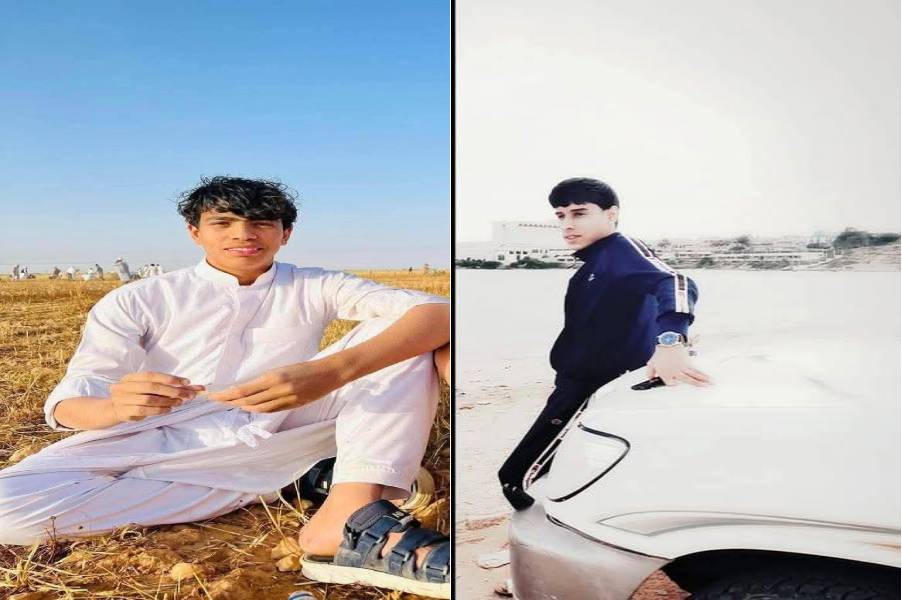

Youssef Eid Fadl al-Sarhani and Faraj Rabash al-Fazari, barely 17 and 18 years old respectively, turned themselves in to their unclear fate. After three police officers were killed during a raid in Matrouh Governorate, Egyptian security forces detained 23 women—relatives of suspects—in what locals say was a hostage tactic to coerce the accused into surrendering.

In a fateful moment overseen by family elders and tribal sheikhs, the two young men decided to surrender themselves to Egyptian authorities in a bid to secure the release of 23 women. The young men maintained their innocence, denying any involvement in the killing of three police officers on April 9, 2025. The following morning, police escorted them to a remote stretch of the desert road to El-Salloum. There, under the scorching sun, they boys were executed—without trial, without evidence, and without mercy.

This was not a scene from a fiction movie; this was real life. The incident followed the killing of police officers from the Matrouh Security Directorate, during a raid to arrest a suspect. According to the testimonies of residents, shared on social media, the police had bargained with the residents, promising to release the detained women in exchange for handing over two of the suspect’s relatives, who would help lead them to his hiding place. Activists and residents took to Facebook with the widespread hashtag (#Except_Women), demanding the release of the 23 women in police detention. They asked, “When did taking women as hostages become acceptable law enforcement?” - calling the incident “a violation of the sanctity of the families and the law.”

Nevertheless, the residents of the village of Al-Nagila heeded the police’s calls. They chose two young men from the family and handed them over on April 10, in the presence and with the mediation of parliamentarians, tribal sheikhs, and mayors in Matrouh. But the very next day, they learned that the two young men had been executed.

The police were quick to offer excuses, claiming in a statement on the official Facebook page of the Egyptian Ministry of Interior that "the criminal investigation departments of the Matrouh Security Directorate, in conjunction with the Public Security Sector, were able to locate the hiding place of two extremely dangerous criminals, perpetrators of the crime of killing three police officers in the Matrouh Security Directorate as they were pursuing an extremely dangerous criminal after a judicial sentences against him.” The statement continued, “The [security forces] were targeted, together with the Central Security Sector, and an exchange of fire resulted in the deaths of the perpetrators, who were in possession of two rifles and ammunition.” This statement and the killing of the two young men sparked widespread public fury among the residents, who denied the police's account in numerous social media posts and reels.

The police had bargained with the residents, promising to release the detained women in exchange for handing over two of the suspect’s relatives, who would help lead them to his hiding place. Activists and residents took to Facebook with the hashtag (#Except_Women), demanding the release of the 23 women in police detention. They asked, “When did taking women as hostages become acceptable law enforcement?” - calling the incident “a violation of the sanctity of the families and the law.”

The Arab Center for the Independence of the Judiciary and the Legal Profession (ACIJLP), led by prominent human rights lawyer Nasser Amin, issued a strongly worded condemnation in a statement circulated through email messages. The Center described the police’s actions as "a grave violation of the right to liberty and bodily integrity,” adding that extrajudicial killings are prohibited under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and constitutes a breach of Egypt's international obligations and a violation of the constitution and Egyptian and international law.

Former presidential candidate Gamila Ismail condemned, in a Facebook post, the murders of the police officers and the young men’s execution, demanding immediate investigations into the incidents.

The Revolutionary Socialists Movement echoed these sentiments, describing the Al-Nagila incident as part of a broader pattern of state violence. “This crime reflects the brutality of a regime that represses under the guise of law and order,” the group said, adding that “the exploitation of women as pawns continues, revealing the extent of the violations suffered by the families of victims in Matrouh. Popular struggle against state terrorism has the power to break this oppressive cycle and hold the killers and criminals accountable in this incident and others. State terror in Matrouh reveals a terrifying level of political tyranny in Egypt.”

Another Death in Police Custody

On April 12, Egyptians awoke to tragic news: the family of twenty-something year old Mahmoud Asaad announced that he had passed away while in custody at the Khalifa Police Station in Cairo. He had been arrested during the first week of Ramadan. The family accused police officers of torturing him to death, citing visible signs of abuse on his body in a video shared from the morgue.

The Ministry of Interior denied these claims. In an official statement, it said that Mahmoud had been detained by order of the Public Prosecution in connection with a drug trafficking case. According to the ministry, a fight broke out between Mahmoud and other detainees, prompting his transfer to solitary confinement. He allegedly grew agitated and was taken to the hospital, where he later died.

According to the non-governmental organization Egyptian Network for Human Rights, officers at Khalifa Police Station threatened detainees who witnessed the incident. The network reported that police warned these eyewitnesses—before they could testify to the prosecution—that they would face fabricated charges if they spoke out. The report also alleged that officers contacted the families and wives of the witnesses to pressure them into changing their statements.

During President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s rule, deaths in detention became more frequent, according to the Egyptian Front for Human Rights. The motives behind torture that leads to death include pressuring victims, who are often from marginalized or working-class backgrounds, to work as informants. Political activists or detainees are also tortured in an attempt to force out sensitive information or confessions under duress.

According to a Justice Committee statement issued on April 29, the number of prisoners and detainees who have died in Egyptian detention facilities since the beginning of 2025 has risen to approximately 13. This follows 50 documented deaths in detention in 2024.

The Justice Committee, a human rights organization based outside Egypt, documented additional deaths in custody during the same week. On April 11, a political detainee who had spent nearly a decade in prison, named Yasser Mohamed al-Khashab, died at Badr Prison Hospital. Just two days earlier, on April 9, political prisoner Mohamed Hassan Hilal died at Qasr al-Aini Hospital after being transferred from Badr 3 Prison in critical condition. There is strong suspicion he was subjected to lethal torture or extrajudicial execution while in custody.

According to a Justice Committee statement issued on April 29, these deaths bring the number of prisoners and detainees who have died in Egyptian detention facilities since the beginning of 2025 to approximately 13. This follows 50 documented deaths in detention in 2024.

What Is Happening Inside Egypt’s Detention Centers?

Since the current regime came to power, the number of reported deaths inside police stations and detention centers has significantly increased—surpassing even the rates seen during the era of former President Mohammad Hosni Mubarak. Human rights advocates note that, prior to the January 2011 revolution, cases of in-custody deaths were underreported, largely due to limited media coverage and access. Moreover, state security agencies often recruited medical personnel during interrogations, who intervened when torture intensified, thereby keeping fatal outcomes relatively low. Among the few high-profile cases that caused public uproar pre-2011 were the deaths of Khaled Said and Sayed Bilal under torture – cases that helped galvanize the Egyptian revolution.

Since then, and particularly during President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s rule, deaths in detention have become more frequent, according to the Egyptian Front for Human Rights. The motives behind torture that leads to death vary. Reasons include pressuring victims, who are often from marginalized or working-class backgrounds, to work as informants. Political activists or detainees are also tortured in an attempt to force out sensitive information or confessions under duress.

According to the non-governmental organization Egyptian Network for Human Rights, officers at Khalifa Police Station threatened detainees who witnessed the incident with fabricated charges if they spoke out. The report also alleged that officers contacted the families and wives of the witnesses to pressure them into changing their statements.

El Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture reported in May 2024 that it had recorded 314 violations, including six deaths due to medical negligence and poor detention conditions, in addition to nine cases of torture.

While there is often ambiguity surrounding the circumstances of these deaths, family testimonies and accounts from fellow inmates have allowed human rights organizations to document numerous violations. For example, the El Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture reported in May 2024 that it had recorded 314 violations, including six deaths due to medical negligence and poor detention conditions, in addition to nine cases of torture.

These figures reflect more than isolated incidents—they reveal a systemic pattern of abuse and a troubling absence of legal accountability in Egypt. The continued use of extrajudicial killings, torture, and coercive tactics such as holding women hostage demonstrate that security objectives are being pursued through illegal and violent means. These practices not only endanger lives but erode the rule of law and human rights in Egypt, raising urgent questions about the need for accountability and immediate intervention.

Translated from arabic by Sabah Jalloul